Decision Journaling: Lessons from Great Thinkers

Enhance your decision-making skills through journaling by reflecting on choices, recognizing patterns, and learning from historical thinkers.

Explore More

Continue your journey:

- How to Start Journaling in 2026 — The complete guide

Explore More

Continue your journey:

- Productivity Journaling: 50+ Prompts — The complete guide

📌 TL;DR — Decision Journaling from Great Thinkers

Great thinkers throughout history have used decision journals. Key lessons: record your reasoning, not just decisions—future learning requires understanding your thinking. Include: expected outcomes, confidence level, and emotional state. Review after outcomes to learn from patterns. The goal: turn every decision into data for better future decisions.

Want to make better decisions? Start writing them down. Decision journaling is a simple practice where you document your choices, reasoning, and expectations. This helps you spot patterns, avoid biases, and improve over time.

Here’s why it works:

- Clarity: Writing clears mental clutter and organizes your thoughts.

- Learning: Reviewing past decisions reveals trends - what works, what doesn’t.

- Confidence: A structured process reduces second-guessing and mental fatigue.

Historical figures like Benjamin Franklin and Marcus Aurelius used journaling to refine their thinking. Modern tools, like Life Note, even integrate AI mentors to guide your reflections and connect insights to real actions.

Start small: jot down the "why" behind your choices and review them regularly. Over time, this habit builds sharper judgment and better outcomes.

The Ultimate Guide to Using a Decision Journal

How to Set Up Your Decision Journal

A clear decision journal is key to learn from your past picks and get better at making new choices. By setting up your notes well, you can look back at them and really get why you thought as you did at first.

What to Write Down Each Time

Every note you make should have these parts:

- Date and setting: When and where did you make the choice?

- Issue and limits: Talk about what was going on and any blocks you had.

- Thoughts and guessing: Write down how you thought this through and what you guessed would happen.

- What you thought would happen: Be clear, like "make 15% more money in half a year."

- How sure were you?: Give your sureness a score from 1 to 10.

- Feelings and mind state: Write how you felt - were you okay, worried, or in a rush?

- Other choices you thought of: Write what else you could have done and why you didn't pick those.

How sure you were helps a lot when you look back at your notes. By seeing your old sureness and what actually went down, you can spot trends - do you often think too high of your guess, or are you too shy?

Feelings and mind state matter a lot too. Did being tired or pumped change your choice? Note any body signs, like being tense or moving a lot, to see how your feelings may have changed what you thought.

When you talk about other options, be clear. Say why you didn't pick them and what you guessed wrong about them. This detail helps you see if your thinking was right later on.

When you've got it all down, keep these notes safe to stop changes that come from looking back.

How to Stop Looking Back Bias

Looking back bias can mess up your decision journal. It’s the trick your mind plays that makes you think past events were easy to see coming. To stop this, be strict about putting down your thoughts as they were right then.

- Write right away: Write down your choice as soon as you make it. Even waiting a few days can change your memory, edited by new info or results.

- Say how sure you were: If you were just 60% sure, write that down. Don't change it later to fit what ended up happening.

- Don't change old notes: Never fix what you wrote before, even if looking back changes your mind. If you want to add new thoughts, make a new note. This makes sure your first thoughts stay as they were and shows your real decision process.

The aim is to write your true thoughts and feelings when you made the choice, without the twist of what came after. This truth is what turns your journal into a good tool for learning.

How to Look Back at Old Notes

Going through your decision journal often turns it into a tool for getting better. These times going back can show runs in how you think and make choices.

Monthly reviews are good for seeing patterns while your choices are still new in your mind. For example, do you often think tasks will take less time than they do? Do feelings like stress or joy mess up how you think? Are there folks whose tips often make things turn out better?

In these reviews, check your confidence levels against real results. Are they matching up? For instance, do you get it right 70% of the time when you feel 70% sure? Or do you find you're too hopeful or too wary?

Quarterly deep dives let you look at a wider set of choices. See if some choices have common results. You might see that choices made when you're tired often turn out bad, or that you skip some options that later show to be good ones.

Annual reviews let you see how you've grown in making choices. Compare how sure you were and how right you were from last year to this year. Are your choices getting better? Use this time to write down key lessons in a special "lessons learned" part. A simple log - with dates, types, confidence levels, results, and big points - can show trends over time.

See these reviews as detective work, finding hints at how your mind works in different cases. By often looking at your choices, you'll find good tips on how to make better ones and get better results.

How History's Top Minds Made Choices

All through the past, many big leaders and smart thinkers wrote in journals to face tough choices and get better at making decisions. When we look at their ways, we find old skills that still help us today. These old ways have shaped how we write about decisions now.

How Big Thinkers Wrote in Journals

Benjamin Franklin had a very neat way of writing in a journal. Every day, he would write about how he did on thirteen personal good traits, think about what went well or bad, and check his actions. This habit let him see trends, set goals for getting better, and stay true to his aims.

Franklin's way was simple but worked well: he made a chart with good traits on one side and days on the other. Each night, he looked at where he did not do well and wrote down what drove his choices and how he could do better in the future.

Jeff Bezos, on the other side, wants to be clear before making big choices. He writes long notes about what he thinks, what might happen, and what risks he might face. These notes make him think hard and act as a record to see how well his choices worked later.

Samuel Pepys is another person from history who wrote a lot in his journal. From 1660 to 1669, he wrote about his day-to-day life, noting big events like the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London, and daily choices about money and home life.

What made Pepys stand out was his focus on both big and small choices. This habit helped him find trends in how he made choices that would have stayed hidden.

Josh Waitzkin, known for his smart thinking, writes in journals to pull apart tough problems into clear questions and actions. He writes before sleep and looks at his words in the morning, letting his mind sort through issues while he rests. This shows how important timing is when you think back, a thing you can also do every day.

Methods You Can Use Now

These old stories show that good journal writing is not just random notes - it's about planned thinking back. Here are some methods from these smart minds that you can try in your own life:

- The Franklin Method: Make a tracker to keep an eye on how you do in qualities you want to build. Take a few minutes each night to think about your day.

- The Bezos Approach: Write long notes before you make big choices. List why you think so, what you expect to happen, and any risks you see.

- The Pepys Strategy: Keep a log of choices about things like money, how you use time, and relationships. Over time, this helps you see repeating trends.

- The Waitzkin Technique: Write about tough choices or problems before sleep and look at your thoughts in the morning for new ideas.

Studies back the thought that writing in a journal can boost self-thinking, control of feelings, and deep thought - skills key to make better choices. Many top folks say journaling helps them stay neat, see clear, and fine-tune their calls. Research also finds that writing to reflect is strong for handling feelings and learning from old times.

The key to doing well isn't being flawless - it's being steady. Big past names like Leonardo da Vinci, Mark Twain, Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, John D. Rockefeller, George Patton, John Adams, Winston Churchill, and Ernest Hemingway all kept up with regular self-think and true checks on what they did.

If you're just starting with a journal, start bit by bit. Give just five minutes a day to try one of these ways. The aim isn't to copy these ways just as they are but to use their main ideas to meet your own hard spots and aims.

Modern Tools for Better Decision Journaling

In earlier sections, we explored how writing down decisions can lead to better outcomes. Now, with the help of digital tools, this practice has evolved into something even more dynamic. These tools don't just help you document your thoughts - they analyze patterns, provide feedback, and connect your reflections to actionable steps, turning decision journaling into an interactive and insightful process.

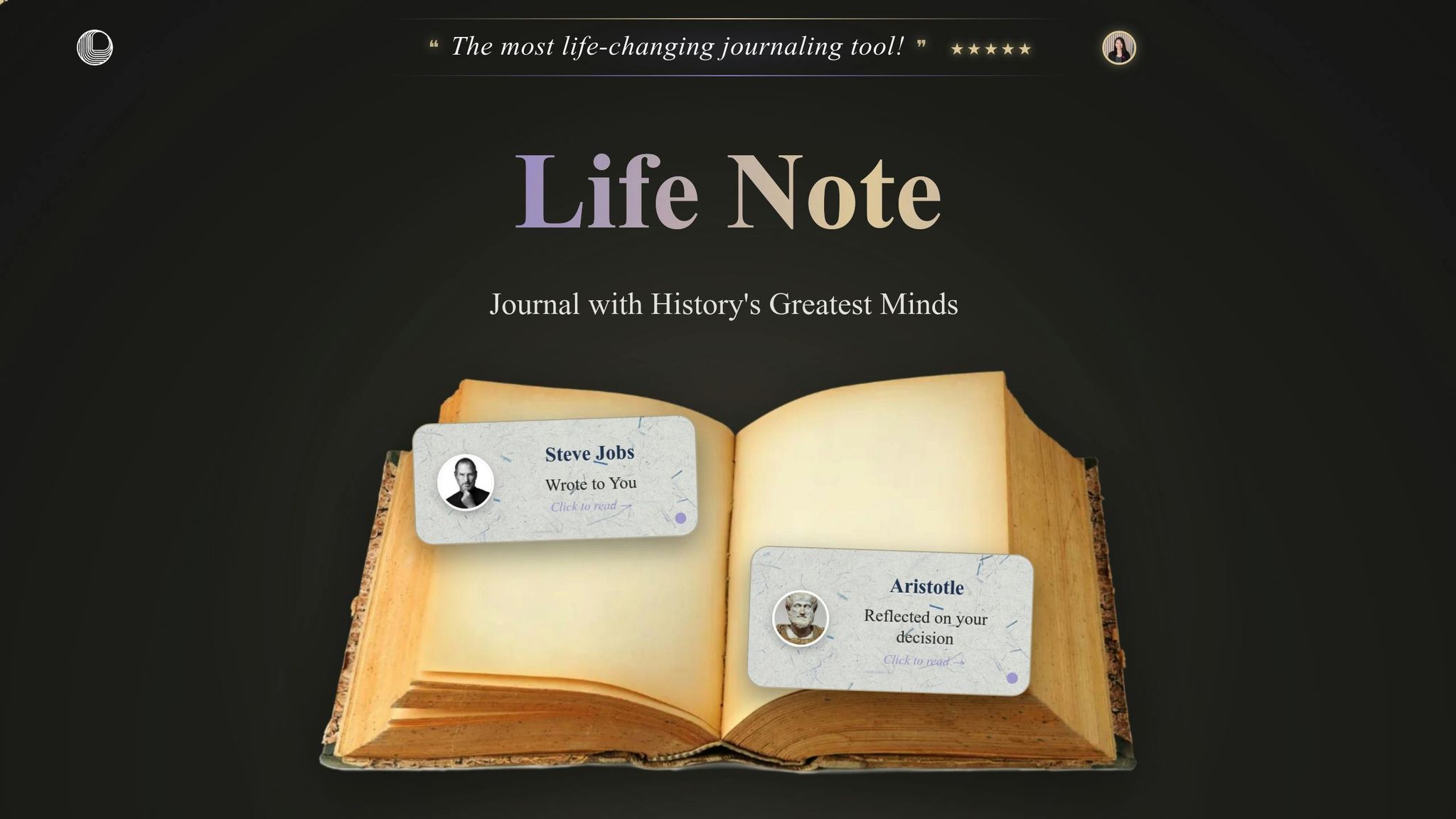

Life Note: Journal with History's Greatest Minds

Life Note transforms journaling from a solitary activity into a lively exchange with some of history's most brilliant thinkers. Imagine having AI mentors inspired by figures like Steve Jobs, Carl Jung, or Aristotle, offering their unique perspectives to guide your decision-making.

When you're grappling with a tough choice, Life Note matches you with a mentor whose expertise aligns with your situation. Their responses reflect their distinct worldviews and mental models, introducing you to ideas you might not have considered on your own.

For instance, if you're debating a career move, Carl Jung might prompt you to explore themes of personal growth and self-discovery, while Brené Brown could encourage you to embrace vulnerability and courage. These mentors provide thought-provoking questions, insights rooted in their philosophies, and practical suggestions to help you weigh your options with clarity.

"I love how tailored the responses are and also the fact that it 'remembers' what I wrote in the previous entries 🤯 It really feels like my mentor is on this journey with me." - Tiffany Durham, Journaling Practitioner

This approach helps break free from the limitations of a single perspective. By engaging with a variety of mental models, you can discover new ways of thinking and overcome mental roadblocks.

Features That Improve Decision-Making

Life Note doesn't stop at personalized mentoring - it takes decision journaling to the next level with features designed to enhance self-awareness and growth. For example, the platform’s memory system ensures that your mentors "remember" your previous entries. This allows them to reference past decisions, recurring patterns, and emotional themes in their guidance.

Every week, you'll receive a personalized reflection from your mentor summarizing your recent entries. These reflections highlight your progress, pinpoint recurring challenges, and offer tailored advice for future decisions. This constant feedback loop not only sharpens your judgment but also helps you track your growth over time.

Life Note also includes tools like the Wisdom Library, which organizes your key reflections, and the Inner Gallery, a visual representation of your personal development.

Turning Reflection into Action

One common pitfall of journaling is the gap between gaining insights and applying them in real life. Life Note bridges this gap with Aligned Actions - personalized, science-backed steps that connect your reflections to tangible changes. For instance, after journaling about a challenging relationship, you might be encouraged to initiate a specific conversation or set a clear boundary, taking inspiration from historical figures who turned reflection into action.

"Life Note has helped me immensely in overcoming complicated mental and emotional issues. What truly captivates me is its ability to develop into a fully mentored path, allowing my pick of inspiring role models." - Faisal Humayun, Senior Manager

Privacy is a top priority. Life Note ensures that your reflections are encrypted and fully under your control, giving you the freedom to explore your thoughts honestly and without concern.

The benefits of this approach are backed by research. A 2022 survey by the American Psychological Association found that reflective journaling led to a 23% increase in clarity and confidence in decision-making among regular users [APA, 2022]. When combined with structured feedback and pattern recognition, these benefits become even more impactful.

Building Better Judgment Through Journaling

Expanding on earlier discussions about decision journaling, this section explores into how regular journaling can sharpen your judgment over time. By reflecting on your decisions consistently, you create a feedback loop that enhances your ability to make sound choices with every new entry.

A study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology revealed that individuals who journal about their decisions and thought processes saw a 23% improvement in decision-making accuracy within six months compared to those who didn’t journal[2]. Similarly, the American Psychological Association found that 68% of participants who engaged in reflective journaling reported greater clarity and confidence in their choices.

One of the key benefits of this practice is recognizing patterns in your decision-making. By documenting your reasoning, predictions, and emotional state, you start to see recurring themes. For instance, you might notice that stress leads to impulsive decisions or that your best choices come after considering diverse perspectives. These patterns form the building blocks of your personal decision-making framework.

Josh Waitzkin, known for excelling in high-pressure environments, uses journaling to break down complex decisions. His approach involves writing at night to process his thoughts and reviewing them in the morning, allowing his subconscious to contribute to problem-solving[1].

To make the most of decision journaling, effective entries should include details such as context, objectives, available options, reasoning, predictions, and emotional state. This structure enables honest post-decision reviews, helping you pinpoint where your thinking was strong and where it might have faltered[2].

Modern tools, like Life Note, take journaling to the next level by introducing new perspectives into your reflections. For example, AI mentors trained on the philosophies of Carl Jung, Steve Jobs, or Aristotle can expose you to diverse mental models and ways of thinking. This isn’t just about receiving advice - it’s about expanding your cognitive toolkit.

"Having the voices of luminaries from different fields comment on my writing has been a major advantage - deepening the experience and helping me gain insights beyond my own words."

- Sergio Rodriguez Castillo, Licensed Psychotherapist & University Professor

Life Note’s advanced memory system adds another layer of depth to your journaling experience. By remembering past entries, these AI mentors can highlight recurring patterns and reference earlier decisions, offering insights you might not catch on your own. Weekly reflection summaries further organize your progress, creating a structured feedback loop that traditional journaling lacks.

The platform also bridges the gap between reflection and action. Its Aligned Actions feature turns your insights into practical steps. For example, if you notice a habit of rushing decisions under stress, the tool might suggest implementing a rule to pause and reflect before making major choices. This transforms self-awareness into meaningful behavioral change.

Journaling to improve judgment isn’t about striving for perfection - it’s about fostering conscious growth. Each entry helps you better understand not just what you decided, but also how you think, what influences you, and where you might have blind spots. Over time, this awareness evolves into wisdom, enabling you to make clearer and more confident decisions.

FAQs

How does decision journaling help uncover biases and enhance decision-making over time?

Decision journaling is a powerful way to step back and examine your own thought process. It helps you spot patterns, biases, and recurring themes in how you make decisions. By looking back at your past entries, you can better understand how emotions, assumptions, or outside influences have played a role in shaping your choices.

With Life Note, mentors provide guidance as you reflect on these moments, sharing timeless wisdom and perspectives from some of history’s greatest minds. Over time, this practice sharpens your ability to recognize personal biases and equips you to make decisions that are more thoughtful and balanced.

How can lessons from historical thinkers improve modern decision journaling?

Historical figures such as Marcus Aurelius, Leonardo da Vinci, and Benjamin Franklin turned to journaling as a way to reflect, gain clarity, and grow. By writing down their thoughts, examining their choices, and learning from their experiences, they cultivated greater self-awareness and improved their decision-making abilities.

Today, decision journaling builds on these age-old practices, encouraging reflection on your choices, analysis of outcomes, and recognition of patterns over time. It’s a powerful way to tap into your inner clarity, align your actions with your core values, and face challenges with a thoughtful and enduring mindset.

How does Life Note transform journaling and help with better decision-making?

Life Note elevates the journaling experience by weaving in AI-guided reflections inspired by both historical and contemporary thinkers. It helps you uncover meaningful insights by identifying patterns in your thoughts, emotions, and experiences over time.

With standout features like a Wisdom Library for revisiting key lessons, tailored weekly reflections, and artistic visualizations of your personal journey, Life Note turns self-reflection into a captivating and rewarding process. By blending timeless wisdom with practical guidance, it equips you to make more thoughtful and intentional decisions.

Related Blog Posts

Journal with 1,000+ of History's Greatest Minds

Marcus Aurelius, Maya Angelou, Carl Jung — real wisdom from real thinkers, not internet summaries. A licensed psychotherapist called it "life-changing."

Try Life Note Free